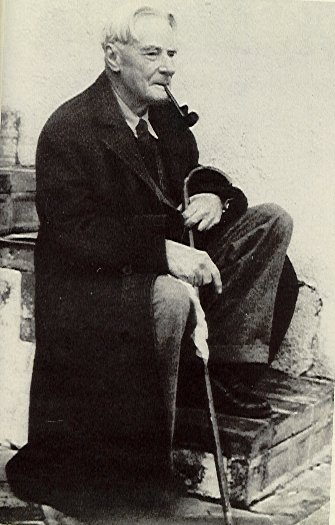

The British fiction-writer and essayist Norman Douglas (b. Thüringen, 1868; d. Capri, 1952) was a cosmopolitan traveller who chose to become a professional novelist and travel-writer. He travelled the length and breadth of the south, and wrote several books on the area which are deservedly famous both in Britain and abroad – they include Siren Land (1911), South Wind (1917) and Old Calabria (1915), which is the finest. Douglas visited Italy for the first time in 1888, at the age of 20. For him, as for many other Northerners, the trip was both a physical and a spiritual rebirth. In 1896 he bought a villa at Gaiola, on the very point of the promontory of Posillipo in Naples, and called it the Villa Maya. Douglas was a diplomat placed en disponibilité and he had no great wish to return to his post in St Petersburg. He lived at the Villa Maya until 1904, when, divorced and impoverished, he moved to Capri and the Villa Daphne. He visited Calabria for the first time in 1907 and returned in 1911. In 1937 he returned once more to Calabria – he loved the wild countryside, the crystal-clear seas, the proud nature of its inhabitants and the many superimposed layers of history. He was interested in everything, fearless, shrewd and undaunted by hardship. He was also a polyglot, sexually unorthodox, a keen observer of social customs and a political reformer. He was conservative but mixed freely with all classes, a great gentleman, yet democratic and approachable, with an unsentimental human warmth. Reading Douglas’ books, with their striking capacity to preserve the tone, the language, the unpredictability of a conversation between friends, is a genuine human experience – heartening, instructive and entertaining.

Douglas wrote Old Calabria in a small furnished room on the outskirts of London and in the legendary reading-room of the British Museum. Old Calabria is not only a great travel book; it is also a useful and up-to-date ‘encyclopaedia’ of a region whose history and more recent development Douglas came to know in the course of several visits he made in the early decades of the twentieth century; it serves as a wonderful introduction to the region. The range of Douglas’ interests, as reflected in the book, is striking. Everything Douglas sees matters to him; he is never indifferent or inattentive. He is fascinated by churches – as long as they are austere and very old – and the ruins of vast, once famous monasteries, and the Albanian liturgical rites. But Douglas is also an acute and penetrating observer of secular, everyday life in Calabria. His curiosity is aroused by the distribution of wealth and the mysterious use of huge fortunes amassed in distant and unexpected villages. He is captivated by the use of Italian and dialect, devoting heart-felt pages to the miraculous survival of a medieval Greek dialect which turns out to be the living legacy of Byzantium. The evidence of a semi-underground intellectual life in Calabria, as revealed in vast scholarly tomes, or in local newspapers as enterprising as they are short-lived, fascinates him and he is careful to document it. Douglas’ customary restrained lyricism is only abandoned when he is in the presence of the Calabrian countryside. The pages of Old Calabria are accompanied by the background music of gurgling streams, just as the translucent, blinding light of the summer sun’s reflections on a once-Greek sea steadily illuminates them – so much so that when Douglas takes us up to the ‘venerable granite plateau’ of the Sila and invites us to join him under the Calabrian pines, we almost shiver at the abrupt transition from light to shade, from burning summer heat to refreshing cool.

All rights reserved: photographic archive, texts and translations.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED, ARCCORDING TO INTERNATIONAL LAWS AND CONVENTIONS.

Nessun materiale può essere riprodotto senza autorizzazione.

Fondazione Napoli Novantanove | Tel. 081/66.75.99 | Fax 081/66.73.99 | Via Martucci, 69 – 80121 Napoli | P.IVA 04506300633